Most of us wouldn’t want to be without our smartphones. They’ve opened up a new world of information, communication and entertainment at the touch of a screen, and a pocket-sized way to capture, store and share our experiences wherever we are.

But there are trade-offs in the ways we use them. Being alive to the costs, being aware of the illusions and working harder to reduce inequalities can help increase the benefits and mitigate the potential harms – for everyone.

Debate over the risks smartphones pose to public health will continue to rage, but the narrative needs to move beyond simplistic characterisations of good vs evil.

Our phones are better for some things than others – the key is to be able to tell them apart.

There are things all of us could do – for ourselves and for each other – that would help raise awareness, improve digital literacy and ultimately make us smarter with our phones.

A reframing of digital skills

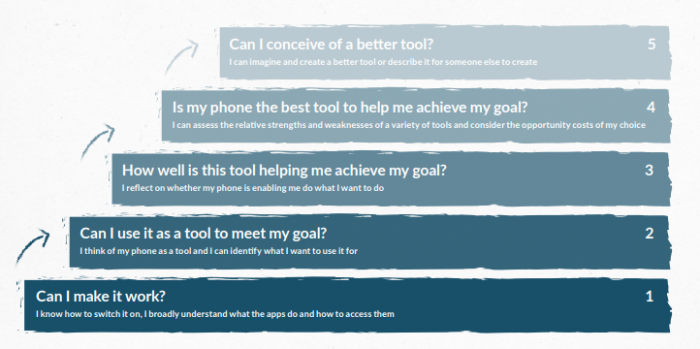

The first thing we could do is rethink what we mean by digital literacy.

Digital skills need to go beyond understanding what technology to use and how to do so to include why, when and even whether to use it.

Digital skills frameworks, whether they’ve been designed for primary school children, disadvantaged teenagers or so-called silver surfers, have tended to focus on how to improve people’s confidence and competency in using applications or software. The device itself is usually not considered – there is an implicit assumption that its use is a good thing.

Our research suggests this is not the best place to start. Before we start talking about how to use a smartphone, we need to encourage people to think of it as a tool. Only then will we actively consider whether it’s the best tool for the job, whether its use is likely to lead to the outcome we want and how we should assess whether it’s done so.

In a world where our smartphones are always in our pockets, these digital skills are just as important – if not more important – as knowing how to use a device. And, like any other skills, they can be taught, and practised, and developed over time.

If the concept of digital skills were reframed to include these prompts and assessments, it would empower us to make more proactive and informed choices about how and when to use our smartphones – and how and when not to.

It this broader conceptualisation of digital skills was role-modelled by parents, taught in schools, understood by health professionals and talked about more widely, it would go some way to lessening the iniquitous effects of reaching unthinkingly for our phones as the go-to means to do pretty much everything.

Ideally it would stop us reaching unthinkingly for our phones at all.

What could teachers do? Teach kids to appreciate the smartphone’s limitations

Teachers really want to help children and young people make the best of technology. This can feel tricky because most teachers didn’t grow up with smartphones themselves.

But just because many young people have had access to phones from an early age, that doesn’t automatically make them the experts in how to use them to their greatest advantage. In fact, the reverse may be true. Old though it is, the adage “If the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” is just as apt in the digital age.

If the definition of digital skills is re-cast to consider the phone as just one tool among many others – digital and non-digital – then being digital natives does not necessarily make young people more digitally skilled than others.

Effective teaching and wider discussion of digital literacy – including an appreciation of the limitations of and alternatives to smartphones – would benefit everyone.

Being digitally skilled means being able to consider not just how to use technology but when – and when it’s probably better not to.

What could parents do? Lead by example

Parents are children’s primary role models. Young people observe and absorb their parents’ behaviours and attitudes – for better and for worse. Just as with healthy eating or attitudes to exercise, parents can lead by example.

This could include starting conversations about what ‘good’ phone use looks like, promoting the idea that the phone is a tool and modelling the use of better tools where appropriate.

What could policy-makers do? Be alive to ‘softer harms’ and productivity gaps

The government is working hard to develop and implement policy that will protect all of us – and particularly young people – from harm. It also explicitly recognises that the effects of technology have an impact on our health and wellbeing.

It is more difficult to legislate against grey areas where technology, content or the behaviour they prompt may have effects that could be considered harmful in some cases, or to some people. But it is essential not to overlook them.

Similarly, being alive to the productivity gaps that smartphone use can lead to – not just in time wasted but in reduced skills and effectiveness – would provide a broader and more powerful narrative connecting technology and health, and individual behaviour and wider society.

What could software providers do? Give users more control

Software providers are, in many ways, as constrained by the limitations of smartphones as everyone else. It makes sense for them to make their software easy to use. But they could give users more choices, more control.

Software companies could prompt us to consider the trade-offs we’re making when we use our phones, and give us options that effectively allow us to prioritise quality of smartphone use over quantity.

What can we all do?

- Think of our phones as a tool

- Consider whether it’s the best tool for the job

- Weigh up the costs or trade-offs we make each time we use it

We all have a choice.

Let’s be smart with our phones.